If you’re getting into the idea of creating your own game it can be hard to know where to start.

Having dabbled with prototyping game ideas for several years now I’m far from being an expert, but I have discovered some pretty useful free programmes and been given some great steers from established designers on everything from testing to design.

This isn’t an exhaustive list by any means, but hopefully it will inspire a few people to get started. In fact it’s 2,500 words but only really scratches the surface - so please do add your own design thoughts in the comments below: I’d love this to be as useful a resource as possible.

10 game design prototype tips

1) Get testing!

This may seem a weird comment, but the biggest barrier to your game design’s future is you. If you have a kernel of an idea - a mechanism you think will work (whether it has a theme attached or not) - then you need to get it to the table.

Don’t do too much in your mind, or even on paper (such as rules and fluff), before really testing your gameplay ideas. Later it will be great Lord Doom was fashioned by the evil wizard in the lava pits of Kzafghyk, but now you need to know if your idea for a tricky Ludo/Mousetrap combat idea will translate into something that’s actually fun - or at the very least might work in a few months when you’ve perfected it.

Here’s the kicker: The more you do without testing, the more time you’ll have wasted when you realise - after five minutes of testing - that it doesn’t work. At all. Or that it’s deathly, deathly dull. Or someone says, “Oh, they use that exact concept in Chess”.

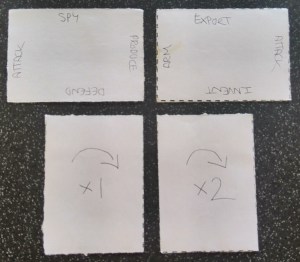

It’s very hard to look at three full books of notes and think, right, let’s try that again. It’s a different story when it’s ten cards written in hand with numbers on. Which leads me to…

2) Keep it simple at first

At this stage you’ll be inflicting your monstrosity (sorry, testing your prototype!) on your best friend, partner or gaming group.

These people know you, love you and will take the piss no matter what you put in front of them - they are not expecting Fantasy Flight components and will not be offering to publish your game at the end of the evening.

Most first prototypes for board and card games can be made with a pad and pen. You don’t need figures, a board, even wooden cubes - cut out bits of paper if you have to. Once you start to want the game to last 30 minutes because the basics are working you can move to the next stage, but for those first short tests you only need basics.

And plan for a short test; there’s no real need to print/write out out all 150 cards you can see in the final version. Star with 20 of the simplest cards (cut up bits of A4 or use note cards for something more sturdy) and see if they work in the way you want them to for a single round of the game. Again if (read: when) you hit problems, it’s so much less to get miserable about! Pop them in the bin and go again.

3) Build your component kit

So you’ve realised the game may be a winner, played a few rounds, and want to take things to the next level. You can print some cards (more on this below) but you also need money, wood, sheep - and player pieces in four or five colours.

The obvious answer is to rob your own board game collection for components. This can work fine - if you’re designing one smallish game. However if the designing bug bites what you’ll end up with is a cupboard stacked with half finished prototypes and a shelf full of unplayable games.

to keep yourself from this predicament, remember charity shops, pound shops and bargain bins are your friends. Some truly terrible (and some great) high street games are brimming with cards, dice and bits you can rescue for your own nefarious means.

Examples: Skip-Bo (numbered cards), Perudo/Liar’s dice (dice), Monopoly (houses), Risk (cubes), poker sets (cards and poker chips) - the list is endless. Just make sure it is super cheap, as otherwise you may be better off just buying the components.

Sometimes you just have to bite the bullet and do the right thing: keep component stores in business. There are so many choices out there, but recently I’ve been very pleased with Magic Madhouse for card sleeves and Spiel Material for cubes.

4) Designing and printing cards

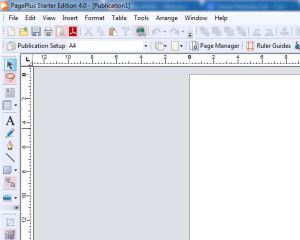

If you’re rich, buy the full Adobe suite of programs including InDesign. Simple. You’re not rich? Me neither. Which is why I use the fantastic free version of Serif PagePlus X9.

If you’ve ever used a desktop publishing (DTP) program you’ll find PagePlus instantly familiar. And the suggestions that you buy it every time you open or close it are a small price to pay for what is an (almost) fully functioned piece of card making software.

If you haven’t used this kind of thing before, it’s actually very simple - a little playing around should see you up and running in no time at all. It opens an A4 blank sheet as default and the create rectangle, text and image insert tools on the left hand side are exactly what you’ve seen in the likes of Word for years.

I’d suggest making a card-sized rectangular box, copy/pasting it until you have a sheet of nine, then saving that as a template. That’s it - happy card making! Even if you don’t want to use the program further you can print these blank cards to cut out and write on.

Of course there’s a downside to most free programs and PagePlus is no exception: but you can easily get around its big issue. Several advanced options are greyed out and only available in the paid version - including saving your files as PDFs. However, you can simply download a program such as FreePDF and choose ‘print’ rather than ‘save’ - choose FreePDF as your ‘printer’ - and it will save your file as a PDF.

5) Making boards

This can be trickier, but essentially the rules outlined above apply. First, your board doesn’t need to be a board at all. Most boards are simply a place to put a collection of game mechanisms - you may find it easier to simply make each part in paper and worry about joining them up into a ‘proper’ board for later versions.

Again, charity shops are your friend. Most game boards are blank on the reverse, so you can move forward by sticking your bits of paper onto the back of an old Monopoly board (or similar).

Alternatively, head back to PagePlus and create your board on four bits of easily printable A4. Selotape them together into a rectangle and you’ll have an A2 board - which is a great size for most tables and standard for many games.

It’s also worth avoiding fiddly board bits, such as score tracks, which are more trouble than they’re worth - especially early on. It’s much better to just Google something: it took me five seconds to find this, for example (pictured). Remember, right now, you’re not selling your game - you’re testing it.

6) Images, fonts and icons

Once your game feels worthy of spending more creative/visual time on, icons can be a great step forward. Any text you can remove (from cards especially) is a good thing, but only if you’re sure the icons help rather than confuse players.

Again, Google is your friend. An image search for ‘icons’ will give you thousands of results, while there are many sites dedicated to listing icons. Some examples are: Game-icons.net, The Noun Project, Icon finder and Vector Stock.

In terms of a prototype, you can use any images you can find - just remember you’ll need permission to use any images if you intent to then commercialise your game yourself (perhaps through a crowd funding platform).

But again only add images that don’t detract from gameplay. Of course some games rely on visuals for the gameplay itself, but remember early on you are usually testing the mechanisms, not visual appeal, so make sure everything is readable in any light. The quicker/easier people can pick up the game, the more useful your testing time will be.

For the same reason, stick to very readable fonts. There are plenty of free font sites out there and a good one can really add to a game’s feel - but can you read it upside down through the murk across a table in the pub?

If you get to the point where you’re showing a game to publishers, there are no hard and fast rules in terms of flashiness of prototype. Most will probably tell you they want them clean, crisp well laid out (not on the backs of cigarette packets) but that art etc doesn’t matter - but then it can’t hurt either.

A bad game is a bad game and no amount of polishing is going to sell that turd. But if there are two great games and one of them is prettier, which is likely to stick in a publisher’s mind? Unfortunately, that simply depends on the publisher.

7) Grow some balls (that includes you, ladies)

The only way your game will flourish is by getting feedback. And as games don’t splurge onto the page fully formed, much of this is likely to be negative - or at least deeply suggestive of change - early on. Don’t be defensive; you’ve asked people to test your game and have to expect things to go wrong. Your skin will soon thicken up, although it can feel really tough at first.

But equally, don’t take feedback at face value. Note it all down, but put it in context. People can’t help themselves but want to win - and their feedback will be from their gameplay perspective. The winner will think it was their skill that did it, not the lack of balance, while the loser may not have enjoyed the game because they got hosed - but because the strategy they tried was underpowered.

That said, you’ll also want to make sure you know the kinds of game people usually like to play. It shouldn’t be surprising if a person who hates auction games doesn’t like your auction mechanic…

Don’t always play. Even better, see if someone else can explain the game while you watch. You can learn a lot watching from body language, the learning curve, ‘aha’ moments - or boredom, disinterest, laughs, tension. It’s a good way to spot where your game shines, or if it has a soggy middle or slow beginning.

If you can find the ‘min-maxers’ amongst your gaming buddies, you’re onto a winner - get them playing your prototype and let them try and break it. Min-maxers are gamers that look for the ultimate way to win and exploit it for all its worth. They don’t just want to win - they want to CRUSH YOU and then tell you how they did it. This makes them great testers, as they can often spot exploits or holes in balance that you missed.

Finally, try and mix up your feedback by letting people speak freely at first - but then directing their thoughts with questions about the things you think you most want to know about. how was game length for example? Was there enough interaction? Did you feel the need to do A, or was B simply too tempting? If you’re trying to home in on one element, you could tell people beforehand what kind of feedback you’re looking for.

8) Hi. My name is Chris and I’m a game designer (“Hi Chris”)

One of the best things about boardgaming is the community - and within it, there’s nothing better than the game design community. People are friendly, happy to help and love testing each other’s games and giving advice.

The obvious place to start are the design forums over at Board Game Geek. Help, chat, competitions, inspirations, theory - even ways to find testers. It’s all there. You may also want to check out Meetup to see if there are any groups in your local area - this is how I got involved and there are more of us out there than you might think!

Discussion and collaboration can be invaluable; especially with more experienced players as well as designers. I’ve played hundreds of different games now but I’m fully aware than many people have played thousands - and even they’ve only scratched the tip of the iceberg.

There are also a good number of international board game competitions you can enter, but I’m working on another post on those so will pass over that area for now.

9) Don’t give up the day job

Remember kids, games doesn’t pay. Yes, some game designers make a living out if doing it full time - but they are either the best, run their own companies or work for someone like Hasbro or Wizards of the Coast. Most do it as a hobby.

If you go into board game design looking to make your fortune, or for a career change, you’re likely to be disappointed. However it’s a fantastically rewarding past-time that could at least pay for itself over time - and even give you the odd holiday! And who knows? Maybe you will become the next big name designer.

But whatever else happens there’s the sense of achievement, the camaraderie, the friendships you’ll forge, the problems you’ll solve, the knowledge you’ll acquire. All in all, as long as you don’t want to get rich quick, it comes highly recommended!

10) Ignore all of the above

But of course the most important thing is that you enjoy the process. If you love whittling individual wooden pieces, or 3D printing elaborate robots made of titanium, knock yourself out - all I’m saying is that to make a game you don’t have to.

I have no idea how many published games use the artwork that was on the prototype the publisher saw when they commissioned it, but I would guess the percentage is infinitesimal. More will keep the theme you thought of, but not all - and you can probably wave goodbye to your lava pits of Kzafghyk story too. But if that drove you to make your game it was all worthwhile.

In the end what’s important is that you do whatever it takes to get your game played - even if it’s only by a few appreciative souls. Much like they say everyone has a novel in them, it’s probably the same for board games. And few things beat the feeling of seeing someone else enjoying something you’ve created. Good luck!

Like this:

Like Loading...